Chapter 15: Emerging Drugs of Abuse

2nd edition as of August 2022

Chapter Overview

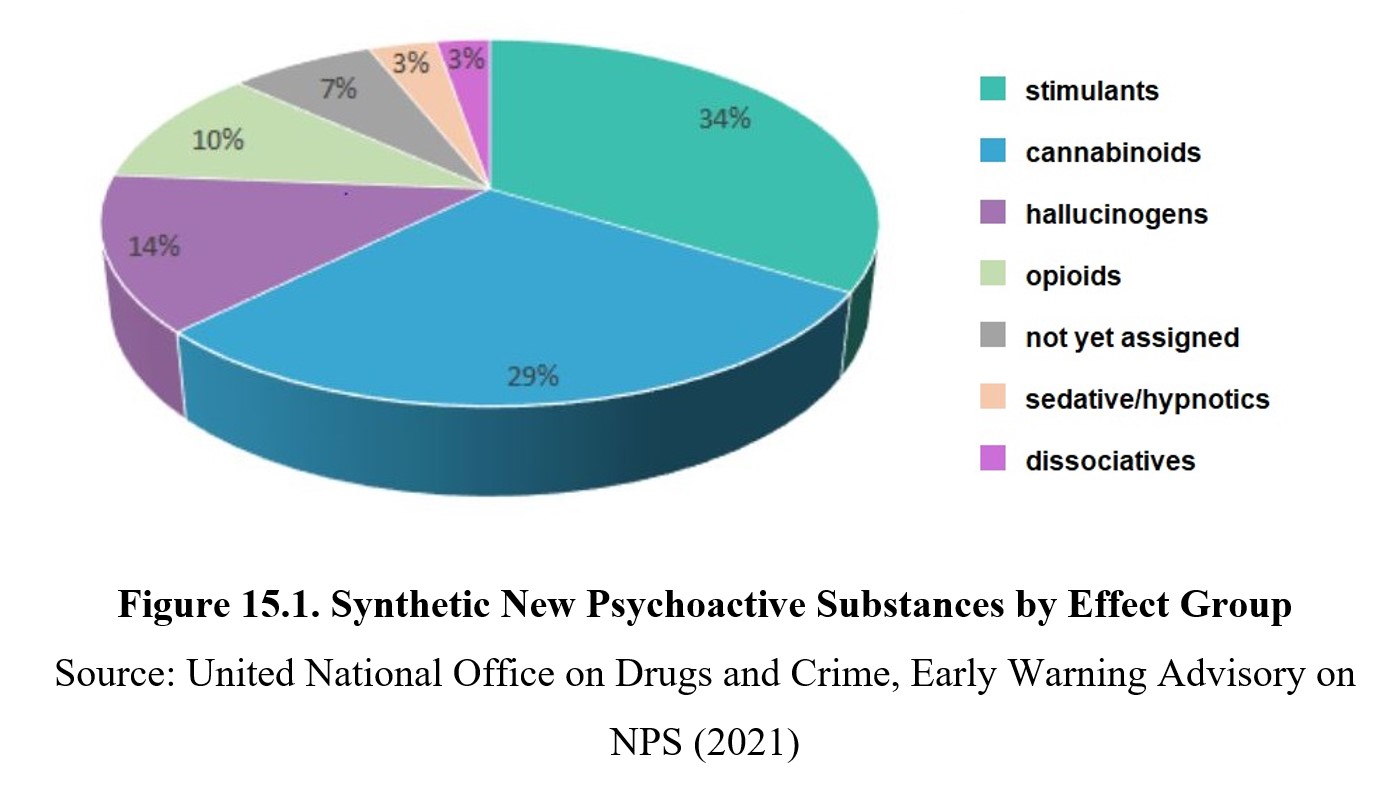

For the final chapter of this unit, we will focus on a heterogeneous collection of drugs identified by the United Nations as New Psychoactive Substances (NPS). In this chapter, we will examine the four types of NPS, synthetic cathinones, synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic hallucinogens, and synthetic opioids. We will also discuss Salvia divinorum and kratom, two substances that are not currently classified as controlled substances but are, nonetheless, listed as substances of interest by the DEA.

Chapter Outline

- 15.1.1. New Psychoactive Substances (NPS)

- 15.1.2. Legal Highs

- 15.1.3. Health Risks of NPS

- 15.2.1. History and Overview

- 15.2.2. Administration and Pharmacokinetics

- 15.2.3. Mechanisms of Action and Effects

- 15.3.1. History and Overview

- 15.3.2. Administration and Pharmacokinetics

- 15.3.3. Mechanisms of Action and Effects

- 15.4.1. History and Overview

- 15.4.2. Administration and Pharmacokinetics

- 15.4.3. Mechanisms of Action and Effects

- 15.5.1. History and Overview

- 15.5.2. Administration and Pharmacokinetics

- 15.5.3. Mechanisms of Action and Effects

- 15.6.1. Salvia divinorum

- 15.6.2. Kratom

Chapter Learning Outcomes

- Define new psychoactive substances, explain why they are not technically illegal, and describe health risks they pose.

- Outline the history of synthetic cathinones and discuss their administration, pharmacokinetics, and mechanisms of action and effects.

- Outline the history of synthetic cannabinoids and discuss their administration, pharmacokinetics, and mechanisms of action and effects.

- Outline the history of synthetic hallucinogenics and discuss their administration, pharmacokinetics, and mechanisms of action and effects.

- Outline the history of synthetic opioids and discuss their administration, pharmacokinetics, and mechanisms of action and effects.

- Describe salvia divinorum and kratom as two additional NPS on the drug scene.

15.1. History and Overview

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) and how they evolved.

- Explain why NPS are advertised as “legal highs,” and why are they so difficult to control.

- Describe the origin, actions, and effects of synthetic cathinones, cannabinoids, hallucinogens, and opioids.

- Explain the differences between marijuana and synthetic cannabinoids.

- Briefly discuss Salvia divinorum and kratom.

New psychoactive substances are clandestinely synthesized compounds intended to mimic the behavioral effects of drugs such as psychostimulants, cannabis, and psychedelics. Because NPS appear on the scene so suddenly, there has not been sufficient research conducted to characterize their pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and adverse effects. Until such information is available, the drugs remain uncontrolled and are advertised as alternatives to illicit drugs or “legal highs.” Once the research catches up with the growing misuse of NPS, serious health risks emerge.

15.1.1. New Psychoactive Substances

According to the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC), New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) are defined as “substances of abuse, either in a pure form or a preparation, that are not controlled by the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs or the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, but which may pose a public health threat.”

UNODC Explains About New Psychoactive Substances [2:06]

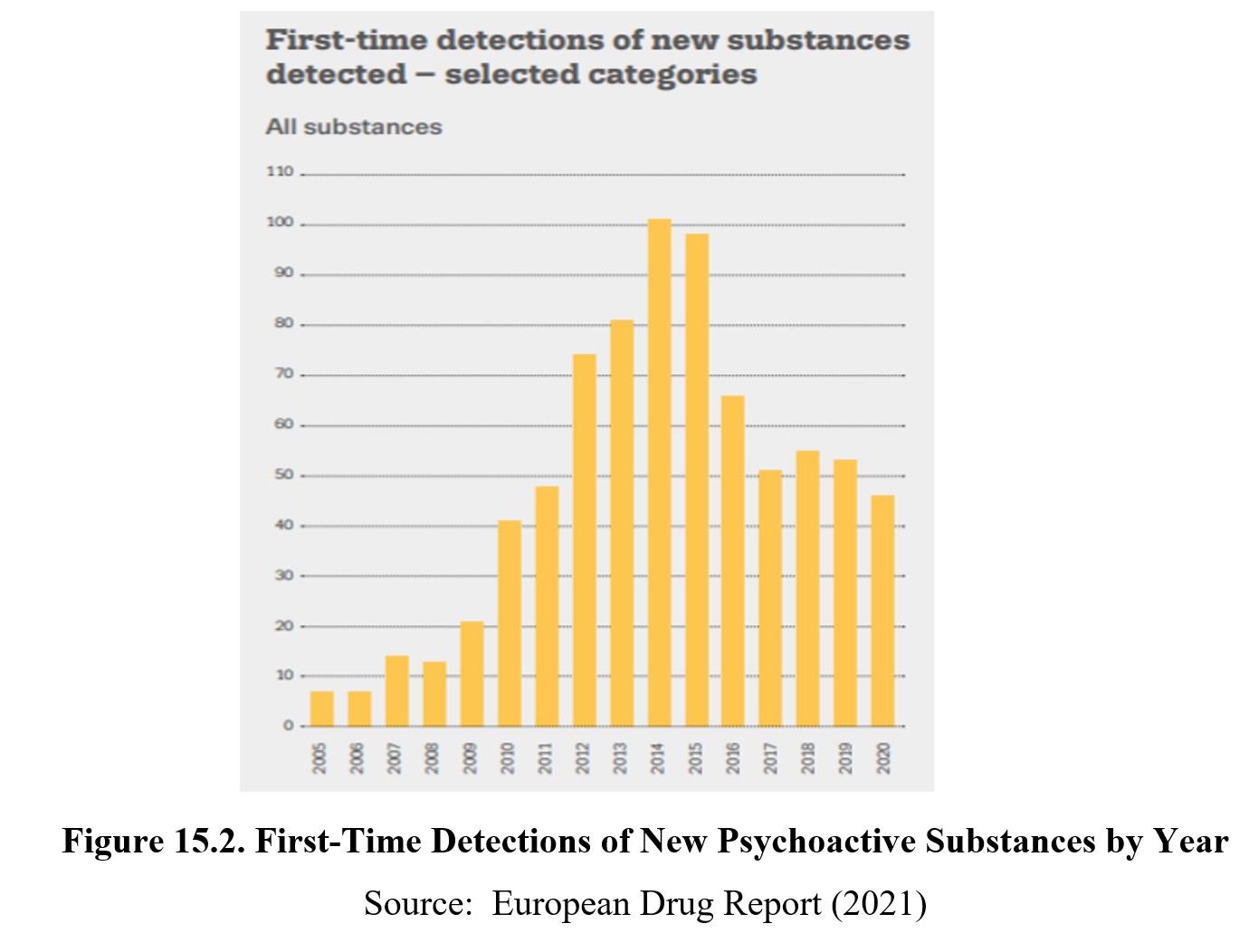

Some NPS were identified decades earlier but are considered “new” due to their more recent emergence as drug problems. Most NPS are indeed “new” because of the explosion of compounds being synthesized by clandestine laboratories and finding their way into the recreational drug market in the mid-2000s. As of January 2020, 120 countries and territories have reported to the United Nations Office of Drug Control (UNDOC) and the European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) the emergence of over 950 NPS worldwide. Just five years earlier, the European Union Early Warning System (EUEWS) reported 560 NPS, attesting to the rapid proliferation of NPS.

15.1.2. Legal Highs

NPS are designed to replicate the behavioral effects of illicit drugs. But because their chemical structures are slightly altered, they are currently unidentified in legislation, which technically makes them not illegal, ergo legal highs. As governments move to limit the spread of NPS through legislation, the drug manufacturers and organized crime are quick to modify the chemistry of these drugs. This results in the introduction of even “newer” NPS to remain a step ahead of the law and avoid being regulated by authorities.

15.1.3. Health Risks of NPS

Although NPS are advertised as legal, they are not necessarily safe. Considering how rapidly illegal laboratories introduce NPS, information about their pharmacological characteristics is sorely lacking. This is further complicated by the lack of quality control and standardization in the synthesis of NPS. The active ingredients of NPS are frequently unidentified. Because the constituents of these NPS are constantly altered, successive batches of the drug may not be identical. Dose-response relationships are uncertain. The toxic effects of extreme doses are not known. Also unknown is the best antidotal drug therapy.

Anxiety, paranoid delusions, seizures, hyperthermia, cardiotoxicity, coma, and death are common health-related complications of NPS. These adverse effects may be exaggerated if the drug user abuses multiple drugs, suffers from mental illness, or has a pre-existing heart or endocrine condition.

NPS are also being used as adulterants of controlled drugs. In some instances, an adulterant is added to the controlled drug to increase profits for the sellers. In some cases, a controlled substance might be replaced with another psychoactive substance.

Given the lack of information about the composition, dose, mechanisms of action of NPS, emergency department physicians are hard-pressed to know how to treat NPS overdoses.

FOX 11 Investigates: Zombie Drugs [4:03]

15.2. Synthetic Cathinones

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the history of synthetic cathinones.

- Explain how synthetic cathinones are administered and their pharmacokinetics.

- Clarify the mechanism of action and the effects of synthetic cathinones.

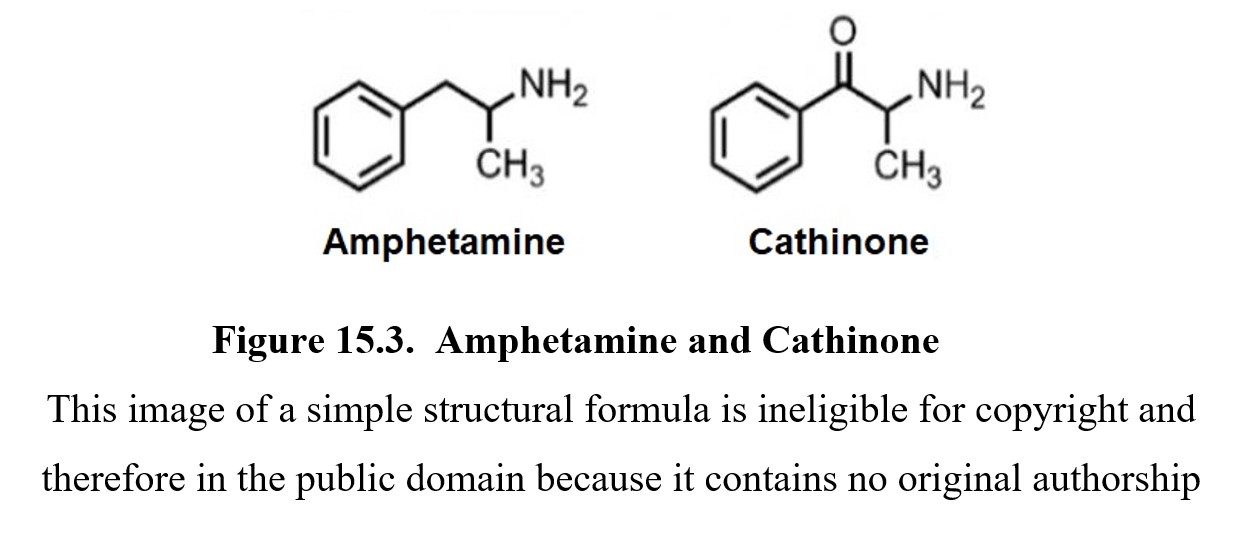

Synthetic cathinones are man-made stimulants that are chemically similar to cathinone, the active psychoactive ingredient of the khat plant Catha edulis. Commonly grown in eastern Africa and the Middle East, it is customary in those locales to chew on fresh or dried khat leaves. It produces stimulant and euphoric effects.

15.2.1. History and Overview

Khat leaves were used in religious ceremonies in ancient Egypt. Until the advent of the 20th Century, the chewing of khat leaves was commonplace in the Middle East. The practice has since spread to the rest of the world. Khat remains a major cash cow in countries such as Ethiopia.

The psychoactive principle in khat is cathinone, which is structurally related to amphetamine. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers khat as a possible drug of abuse but not as addictive as tobacco or alcohol. Khat is effectively banned in the U.S. because cathinone is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance by the FDA. Synthetic cathinones are illegal and typically marketed as bath salts, incense, or plant food. They may also bear labels warning “not intended for human consumption” to avoid liability for use of these products.

15.2.2. Administration and Pharmacokinetics

Synthetic cathinones are usually ingested orally, but insufflation and intravenous injection have also been reported. Common synthetic cathinones include 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV, also known as methylone), 4-methylmethcathinone (4-MMC or MCAT, mephedrone), and alpha-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (alpha-PVP, flakka). These are generally formulated as capsules and tablets. Taking synthetic cathinones typically brings on effects within 15-45 minutes. The effects usually dissipate after 2-4 hours.

15.2.3. Mechanisms of Action and Effects

The mechanism of action of synthetic cathinones is increased dopamine activity in the brain resulting from stimulation of neuronal release of dopamine and prevention of the reuptake of dopamine. This is similar to the psychomotor stimulant action of amphetamine. It may also block the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin.

Recreational doses of bath salts produce light-headedness, euphoria, increased sex drive, memory loss, and reduced appetite. Higher doses are much more dangerous, producing anxiety attacks, paranoid delusions, nausea and vomiting, cardiac arrhythmias, convulsive seizures, and death. The most notorious synthetic cathinone is flakka, which causes “excited delirium”. This condition consists of hyperexcitability, paranoid delusions, hallucinations, and increased strength. Prolonged use of flakka can lead to cardiovascular complications, stroke, aneurysm, and death.

15.3. Synthetic Cannabinoids

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the history of synthetic cannabinoids.

- Explain how synthetic cannabinoids are administered and their pharmacokinetics.

- Clarify the mechanism of action and the effects of synthetic cannabinoids.

Cannabis has a long history of use worldwide. While cannabis is still federally-listed as a Schedule I controlled substance, the legal landscape is changing as more and more states are approving medical marijuana or recreational marijuana. Canada approved medical marijuana in 2001 and legalized recreational marijuana in 2017.

15.3.1. History and Overview

Synthetic cannabinoids found their beginning in the research of Dr. John W. Huffman, who was interested in producing pharmacological tools to target cannabinoid receptors in the body. As a professor of organic chemistry at Clemson University in South Carolina, he developed hundreds of synthetic cannabinoid compounds to study the endogenous cannabinol system and its physiological function.

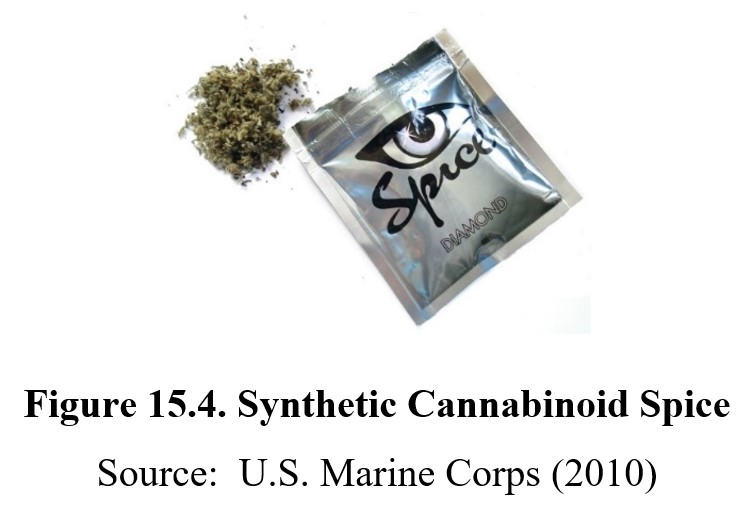

In the early 2000s, Huffman’s research which was published in the scientific literature was hijacked by clandestine chemists. Synthetic cannabinoids began to appear in Europe under the names Spice and K2. They were widely advertised as “legal highs” or “legal marijuana”. These products consist of smokable herbs sprayed with synthetic cannabinoids. Among these was Huffman’s cannabinoid receptor agonist JWH-018, considered to be 3x as potent as THC. Read this interview with John Huffman about his research with synthetic cannabinoids.

15.3.2. Administration and Pharmacokinetics

The most common use of synthetic cannabinoids is to smoke dried plant material that has been sprayed with the compounds. Synthetic cannabinoids are highly lipid-soluble and quickly enter the brain. The high may last 30-120 minutes depending on the dose consumed or inhaled and the specific cannabinoid is taken. The drugs are typically biotransformed in the liver and can be detected in urine samples.

Synthetic Cannabinoids (Spice) [9:20]

15.3.3. Mechanisms of Action and Effects

Synthetic cannabinoid agonists were intended to mimic the actions and effects of D9-THC. These compounds have affinity and efficacy for CB1 and CB2 receptors and, to an extent, produce the same effects as cannabis. However, early in the misuse of synthetic cannabinoids, users noticed several extreme reactions such as tachycardia, nausea and vomiting, agitation, paranoid behavior, and hallucinations. These unexpected effects were experienced by long-time pot smokers.

Since there are no standards for manufacturing, packaging, or sales of synthetic cannabinoids, drug users are in the dark about how much to take or what side effects to expect. Moreover, the quantity and quality of the drug are uncertain.

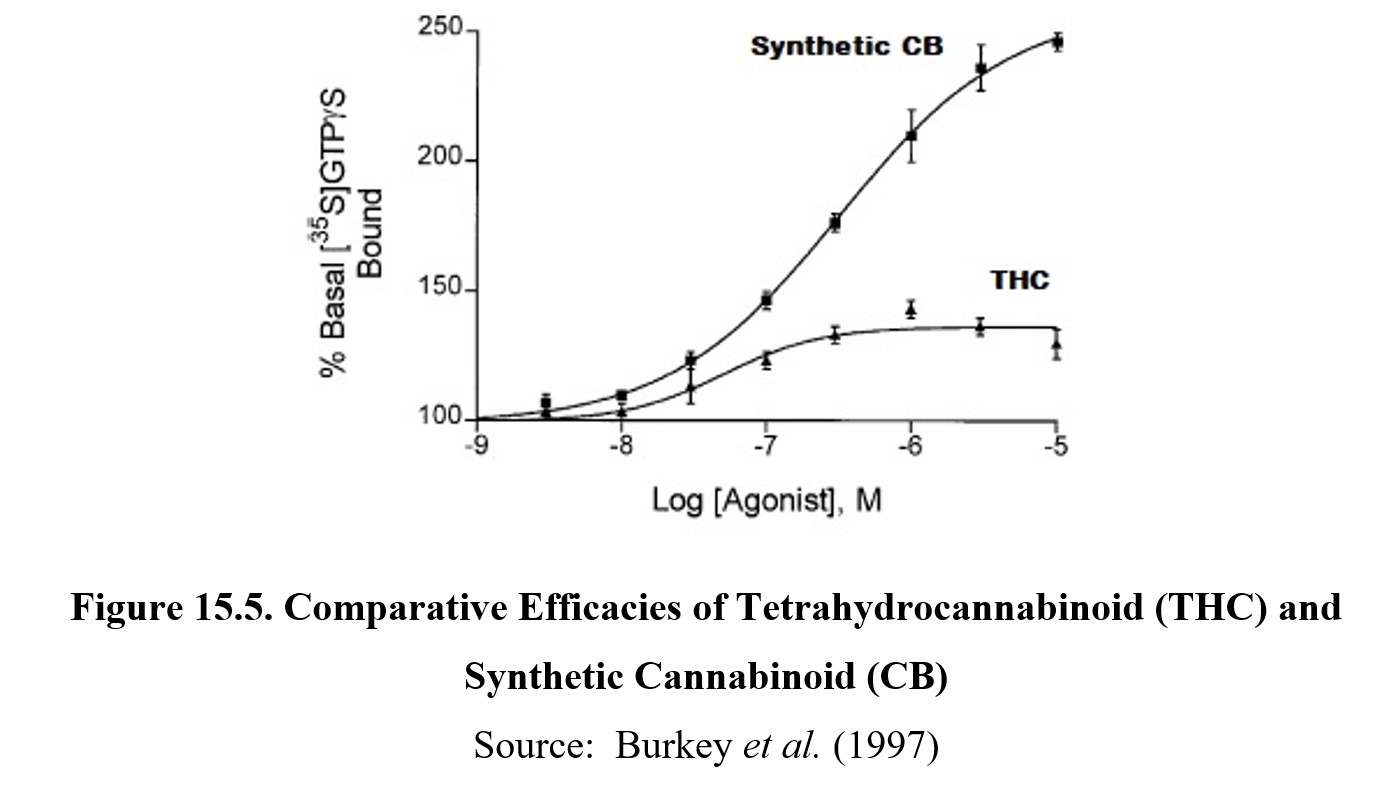

There is also a pharmacological reason for the exaggerated adverse effects of synthetic cannabinoids. Research has demonstrated that THC is only a partial agonist at cannabinoid receptors. Hence, the maximum effects of THC represent the ceiling effect of the drug. Synthetic cannabinoids, on the other hand, are full agonists with a much greater ceiling effect than THC. This is akin to morphine being a full agonist at opioid receptors, while buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the same receptors. Another contributing factor is that a marijuana joint contains multiple phytocannabinoids, including cannabidiol (CBD). CBD is thought to mitigate some of the more negative effects of THC. But if someone smokes Spice, the full spectrum of the synthetic cannabinoid is uncompensated.

Synthetic Cannabinoids vs. Natural Marijuana [2:07]

15.4. Synthetic Hallucinogens

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the history of synthetic hallucinogenics.

- Explain how synthetic hallucinogenics are administered and their pharmacokinetics.

- Clarify the mechanism of action and the effects of synthetic hallucinogenics.

Hallucinogens are a diverse group of compounds ranging from lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) to psilocybin. Synthetic hallucinogenic NPS are man-made compounds intended to produce effects similar to LSD.

15.4.1. History and Overview

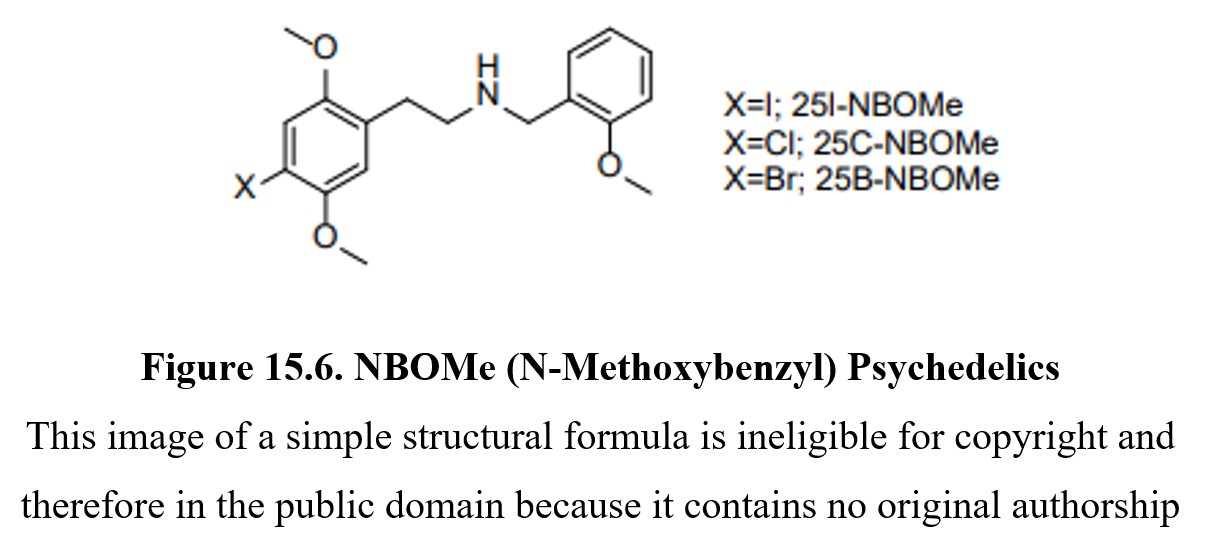

The most prominent synthetic hallucinogen is 2-(4-iodo-2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-N-[(2-methoxy-phenyl)methyl]ethanamine (25I-NBOMe). It was more popularly known as N-bomb, a name that also colloquially includes two closely related compounds, N-(2-methoxybenzyl)-2-(4-chloro-2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)ethanamine (25C-NBOMe) and 4-bromo-2,5-dimethoxy-N-(2-methoxybenzyl)-phenethylamine (25B-NBOMe) (Zawilska et al., 2020). However, 25I-NBOMe is the most frequently abused of these compounds.

NBOMes were originally synthesized as a pharmacological research tool to study serotonin receptors in 2003. But the research was hijacked by clandestine laboratories to produce recreational NPS in 2010. Originally marketed on the streets as a “legal high”, N-bomb resulted in a rapid and significant increase in hospital emergencies. The DEA temporarily listed all three versions of N-bomb as Schedule I controlled substances. In 2016, the classification was made permanent.

15.4.2. Administration and Pharmacokinetics

25I-NBOMe and other N-bombs are usually applied to sheets of blotter paper, not unlike LSD, and are sometimes sold on the streets as LSD. Powder and liquid forms of the drugs have also been discovered, but the most frequent route of administration is sublingual or buccal. Some users have also been known to inject it, smoke it, vaporize it, and inhale it. The average dose of N-bomb is 750 micrograms and is very potent. Taken sublingually, the duration of action of 25I-NBOMe is approximately 6-12 hours, depending on the dose. Because the drug is so potent (750 micrograms is equivalent to a few grains of table salt), it is very easy to take an overdose. The NBOMes undergo extensive biotransformation in the liver often to biologically active byproducts.

15.4.3. Mechanisms of Action and Effects

25I-NBOMe was designed to map the distribution of 5HT2A in the brain by its affinity for the receptor. Pharmacological studies showed that 25I-NBOMe targets the 5HT2A receptor similar to LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. It is also reported to interact with various other neurotransmitter systems in the brain. Psychoactive doses of NBOMes evoke a mild CNS stimulatory effect, euphoria, enhanced sensory perceptions, and other psychedelic effects. Intoxicating doses can produce agitated delirium, panic attack, aggressive and sometimes violent behavior, and suicidality. Severe intoxication can result in coma and multiple organ failure.

15.5. Synthetic Opioids

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the history of synthetic opioids.

- Explain how synthetic opioids are administered and their pharmacokinetics.

- Clarify the mechanism of action and the effects of synthetic opioids.

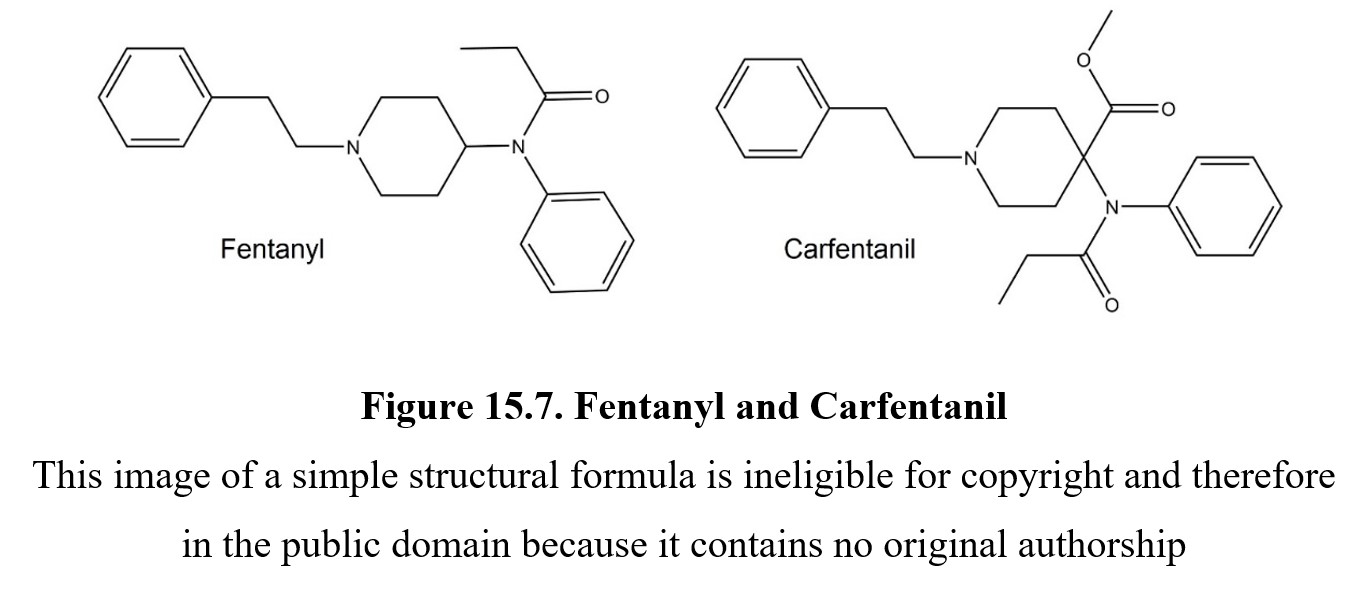

There are three classes of opioids: the original opium alkaloids; the semisynthetic opioids; and the synthetic opioids, which do not bear any structural resemblance to the opiate alkaloids. This group includes methadone which is used in the treatment of opioid use disorder and fentanyl which is used in the treatment of breakthrough pain in cancer patients. Fentanyl is ~80-100´ potency of morphine. When used recreationally, fentanyl produces an intense rush and is sometimes mixed with heroin to increase its potency.

15.5.1. History and Overview

Novel synthetic opioids (NSO) or designer opioids are considered NPS. They include various potent analogs of fentanyl such as carfentanil and newer non-fentanyl compounds. Carfentanil is 10,000´ potency of morphine, and just a few grains of carfentanil can be deadly. This drug is a Schedule II controlled substance because it is approved for use as a veterinary anesthetic for large animals, such as elephants. Carfentanil is not approved for use in humans. However, its emergence in the illicit drug market poses a dangerous new threat in the opioid epidemic. It is the second most abused synthetic opioid after fentanyl.

There is a host of other non-fentanyl-derived NSOs including 2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-N-(2-(dimethyl-amino)cyclohexyl)-N-methylacetamide (U-48800), trans-3,4-dichloro-N-[2-(diethylamino)cyclohexyl]-N-methyl-benzamide (U-49900), 3,4-dichloro-n-{[1-(dimethylamino)-cyclohexyl]methyl}benzamide (AH-7921), and 1-cyclohexyl-4-(1,2-diphenylethyl)piperazine (MT-45).

There was no demand for the creation of these NSO. Still, they suddenly emerged due to online dissemination of their synthesis, e-commerce on the internet, and poor regulation of clandestine laboratories abroad.

15.5.2. Administration and Pharmacokinetics

NSO are usually administered by intravenous injection. These drugs are often adulterants in street heroin or a portion of counterfeit prescription painkillers. Sometimes they are purchased as such by opioid abusers seeking a more intense rush.

15.5.3. Mechanisms of Action and Effects

Like their progenitors, NSO are compounds with affinity and efficacy at mu-opioid receptors. Their pharmacological profiles are similar to other opioid drugs. They can produce analgesia, euphoria, respiratory depression, constipation, and other opioid effects. Repeated use can result in the development of tolerance and dependence. These drugs share a similar toxic syndrome (toxidrome) of pinpoint pupils, coma, and respiratory depression along with hypothermia, hypotension, bradycardia, pale, clammy skin, and bluish discoloration of fingernails and lips. Due to the high potency of NSO, there is a shorter therapeutic window of reversal of overdose by naloxone and a requirement for higher doses of naloxone for the rescue of the subject.

15.6. Other Drugs

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe salvia divinorum and outline its effects.

- Describe kratom and outline its effects.

Two additional NPS that have made their way into the drug scene are salvia and kratom.

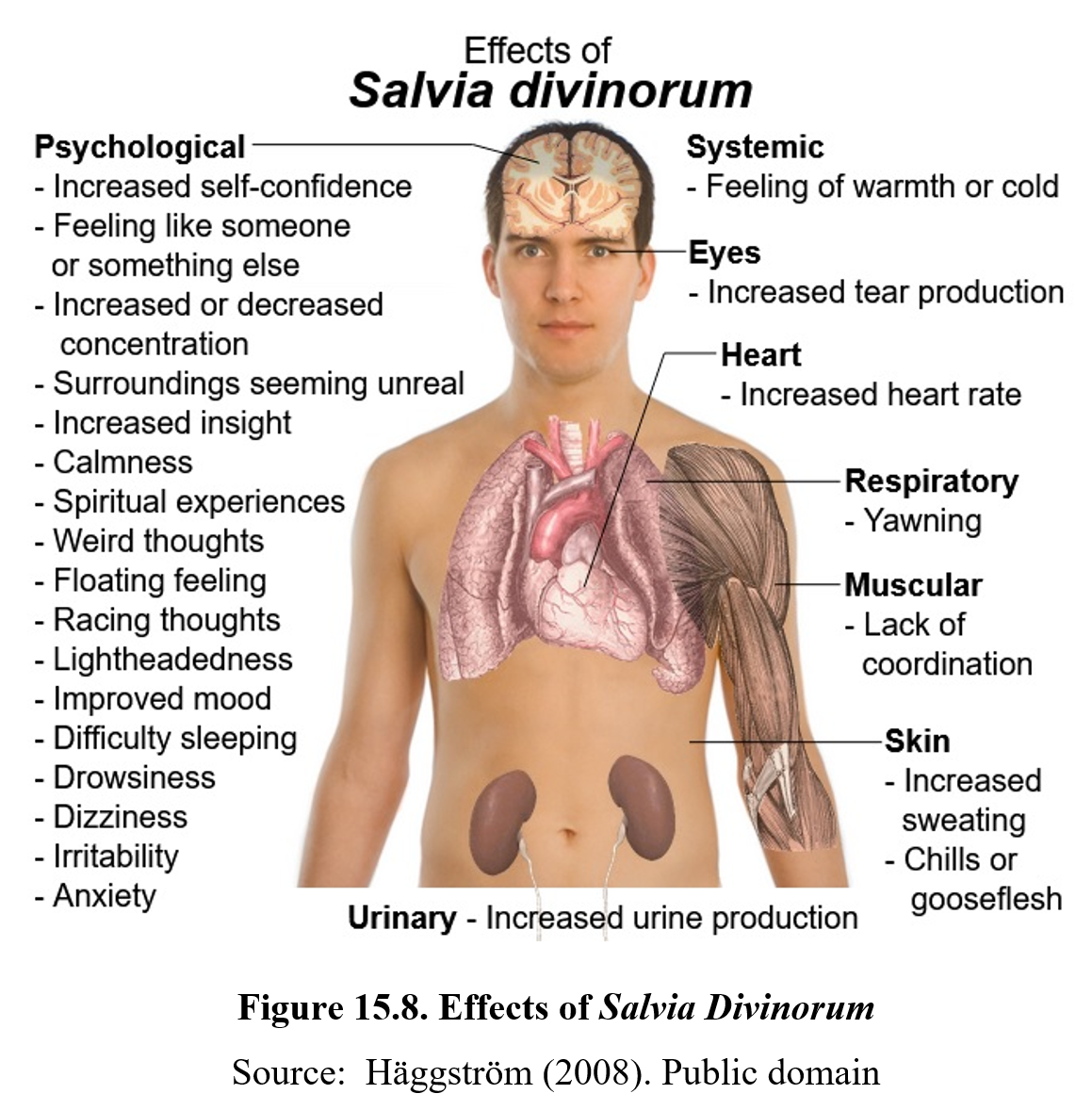

15.6.1. Salvia divinorum

Salvia divinorum is a psychoactive plant originally found in the state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico. Salvia leaves were chewed by the indigenous Mazatec people or grounded and prepared as drinkable tea. Salvia also had a centuries-old history of use by shamans in religious ceremonies. It was also used for medicinal purposes to treat various maladies. Recreational use of salvia most commonly involves smoking from a hookah or water bong. The effect is a very rapid-onset and experience of 15-20 minutes duration. There can be intense hallucinations, synesthesia, detachment from reality, and mood swings.

The major psychoactive component of salvia is the alkaloid salvinorin A, which is a potent kappa-opioid receptor agonist. Since kappa opioid receptors co-localize with many dopamine neuronal systems, salvia can impact higher cognitive functions as well as mood and anxiety.

Salvia is not currently considered a controlled substance by the DEA but is listed as a drug or chemical of concern requiring further investigation. There is a deficiency of knowledge about drug safety and toxicity of salvia. However, at least 29 states have passed legislation banning or regulating salvia. There has been discussion about whether the DEA should classify salvia as a Schedule I controlled substance. If this comes about, scientists fear that research into the pharmacological actions and effects of salvia as well as its potential therapeutic applications will be greatly hampered. This would be similar to the lack of scientific knowledge of basic and beneficial medical properties following marijuana being made a Schedule I controlled substance.

15.6.2. Kratom

The kratom plant (Mitragyna species) is an evergreen that is native to Southeast Asia. People chew kratom leaves or steep the dried or powdered leaves in tea. Its traditional use is to stave off fatigue and improve work productivity. It is also used to treat pain, cough, and diarrhea. But kratom has also emerged as an NPS worldwide. Recreational users of kratom typically ingest it orally. Kratom is frequently advertised as a legal alternative to opioids and is openly sold on the internet and in smoke shops.

The effects of kratom are dose-dependent. At low doses, kratom is a mild stimulant. At high doses, kratom produces sedative and analgesic effects. When abused chronically, kratom can cause tolerance and dependence. Extremely high doses of kratom cause a toxic psychosis with confusion, delusions, hallucinations, and seizures. Long-term use of kratom can result in addiction.

The active ingredients of kratom are mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine (7-HMG) among other alkaloids. It is hypothesized that mitragynine and 7-HMG may be at least partial agonists at kappa-opioid receptors. They may also influence other neurotransmitter systems as well.

At present, kratom is not classified in the DEA Schedule of Controlled Substances through the DEA considers it to be a drug or chemical of concern. The possession and use of kratom in six states is illegal, and in other states, it is legal but regulated. In 2016, the DEA proposed to temporarily classify kratom as a Schedule I controlled substance due to concerns about abuse and safety. This led to a public outcry that resulted in the DEA rescinding its decision for emergency scheduling of the psychoactive ingredients of kratom just two months later.

The FDA does list kratom as an herbal supplement. It is worth mentioning that the FDA regulates dietary supplements according to a different standard than those for foods and medicines. Manufacturers are not required to have their dietary supplements approved by the FDA before producing or marketing their products. However, it is illegal to sell a supplement as a treatment for alleviating symptoms of a specific medical problem. Otherwise, it would all be under the FDA standards for medicines. The role of the FDA relative to supplements is to continue post-marketing surveillance for adverse drug effects.

Chapter Summary and Review

In this chapter, we covered four different classes of NPS: synthetic cathinones, synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic hallucinogens, and novel synthetic opioids. We also introduced two other substances, Salvia divinorum and kratom, which are not regulated by the DEA but are the subject of intense discussion over whether they should be listed in the Schedule of Controlled Substances. We examined examples of NPS in each class and their varied pharmacological properties. This is the final chapter for the third unit.

Chapter 15 Practice Questions

Answer the following questions:

- What are the four main categories of NPS?

- Why are NPS considered “legal highs”?

- Why are NPS considered health hazards?

- What is khat?

- How do manufacturers of synthetic cathinones attempt to evade liability for abuse of their products?

- What is the mechanism of action of synthetic cathinones and what are their effects?

- What is flakka?

- What is excited delirium?

- Who is Dr. John W. Huffman?

- What are Spice and K2?

- Explain the difference between cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids.

- What is N-bomb?

- What is the mechanism of action of synthetic hallucinogens and what are their effects?

- What is the most important drug property of novel synthetic opioids like carfentanil?

- Describe the pharmacological effects of novel synthetic opioids.

- What is Salvia divinorum?

- What are the effects of kratom?

2nd edition